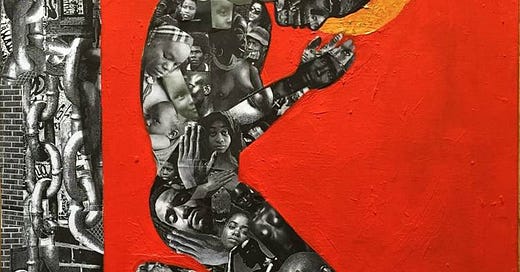

Soft Boy, Hard World: To Be Holy, But Never Whole

On shame, memory, and the weight of spiritual inheritance

About the Series

Soft Boy, Hard World is a slow-burning memoir. A scattered map of the moments that shaped me. In these essays, I return to my teenage years, not for nostalgia, but for excavation. I want to understand how shame and softness coexisted inside a boy who was learning to lie before he learned to love. I want to name the quiet betrayals: the church pew silences, the broken friendships, the moments of beauty that cracked through anyway. Sometimes I’ll write from memory. Sometimes from feeling. Sometimes from the voice of a boy I once was, writing to the man I became.This series is about growing up gay, Black, and soft in places that demanded something harder. It's about artists who offered me refuge. About the habits I formed to survive. About the trust I still struggle to give. Every piece will be different in form, but all of them will ask the same quiet question: What did it cost to survive like this? And who am I still allowed to become?

Tuned to the Same Frequency

The first time I experienced ecstasy, I must have been twelve, maybe thirteen.

I was in church, surrounded by people I loved, our voices lifted and layered like silk. Not just singing with each other, but singing into each other. Swaying in unison as if we’d tuned our souls to the same divine frequency. At some point, it felt like meditating in harmony. And in that moment, belief didn’t feel like a choice — it felt inevitable.

The choir was thunderous. The stained glass behind the pulpit scattered sunlight across their faces like God himself had blessed the lighting design. A full band (bass guitar, piano, drum set, sometimes a saxophone) filled the room, but never overpowered the real centrepiece: the voices. Tones, textures, harmonies that could split you open and leave you grateful. Sometimes they sang alongside the band. Sometimes a cappella. But always powerful.

On that day, they sang:

“I need you, you need me / We're all a part of God's body / You are important to me, I need you to survive.”

And I believed them.

I stood in the middle of the congregation, twelve years old, eyes closed.

Goosebumps. Peace. Joy. Wholeness.

I didn’t know what it meant to be filled with the spirit, but I knew what it meant to disappear into something.

The church was the first place I felt part of a community that reached beyond blood. It gave me language for things I didn’t yet understand: grace, calling, destiny. It held me, even as I was just beginning to understand what I might one day need to hide.

The Rhythm of Belonging

There was a kind of equality when you walked through the doors of my church.

It didn’t matter whether you were a nurse, a cleaner, or the CEO of a multinational. Whether you were Jamaican, American, Ugandan, St. Lucian, Nigerian, Kenyan, South African, Trinidadian or born and raised in London — we were all God’s children. Equal in sin. Equal in grace.

Once inside, you were family. A member of the body. You were just another soul in search of grace, and just like everyone else, you were welcomed with a smile, a firm handshake, and the familiar greeting: Happy Sabbath.

That phrase alone carried weight. It meant the world had been paused for a moment. That no matter how battered your week had left you, you were here now. Clean. Dressed. Ready. Equal in sin, equal in hope.

Church gave shape to the week. It gave you a checkpoint, a time to reflect on your life. To notice your moods. To track your growth. To admit you were overwhelmed or proud or lost or just trying your best. Where else in the world were you invited to sit down for two hours and simply feel — to cry if you needed to, to be prayed for if you were struggling, to testify if things had turned around?

There was a moral stability built into it, too. Not in a finger-wagging way (at least, not always), but in a framework sense. Church taught you how to navigate life with intentionality. To pause before you judge. To speak kindly. To think in service of something greater than yourself. It trained your instincts toward reflection through sermons, through prayer, through simply watching others navigate their own seasons of hardship and healing.

In that space, I learned the art of self-examination. I watched men I admired wrestle openly with disappointment. I saw women offer each other grace when life didn’t go as planned. And I began to understand, however quietly, what it meant to show up for your life.

Looking back now, I realise it was one of the only places in my childhood where reflection was built into the architecture. A stillness is designed into the routine. The world didn’t often give Black children that — a weekly rhythm that said, pause. consider. realign.

And for a while, I did. I aligned myself to it fully. To the rules, the reverence, the rhythm of belonging. Before I understood what I might need to hide, I knew exactly where I belonged.

Doctrine and Doubt

When I was younger, I loved the tangibility of church life. I was obsessed with Scouts, taught through the church, where you could collect badges for skills like knot tying, hiking, camping, and community service. I could pitch a tent, tie a bowline, build a fire, and sing call-and-response songs under a starlit sky, half-hypnotised by the smell of damp earth and smoke.

But as I got older, what drew me in wasn’t the physical challenge; it was the conversation.

Bible study, in particular, captivated me. It was structured like English literature but with a moral compass. Each week, we examined the messiness of human behaviour through ancient texts and collective reflection. It was less about memorising scripture, more about interpretation. Application. Real life. It was about looking into the eyes of someone else and saying: Yes, I’ve felt that too.

We debated the meaning of suffering. Of grief. Of betrayal.

I didn’t know it then, but this was my first introduction to moral philosophy.

Take Job, for instance. A man who lost everything (his children, his wealth, his health) and still clung to the idea that God had a plan. Some weeks, I admired him. Other weeks, I resented him. Because I didn’t understand how faith could coexist with so much pain. But in our group, we didn’t just talk about Job. We talked about grief. About resilience. About what to do when life strips you bare and no comfort comes.

And then there was Peter. The disciple who swore he’d never betray Jesus — and then did, not once but three times. His story was messier. More human. We talked about guilt. About letting down the people we love. About whether redemption is possible when you’ve failed someone or yourself.

Those studies weren’t abstract for me. They were mirrors.

I didn’t say it out loud at the time — not to anyone — but I was already carrying secrets. Questions about myself I couldn’t frame without fear. And so, I looked to the stories we studied not just for answers, but for alignment. For a way to reconcile contradiction. I wondered if Peter had hated himself, even after being forgiven. I wondered whether Job ever doubted God in the dark, even if he never said it aloud.

What made it more powerful was that these weren’t private reflections. They were collective. Shared. We debated with people from all walks of life — elders and teenagers, aunties and returning university students. I watched people cry in front of their community. I watched people hold each other in silence. We weren’t just studying the Bible. We were studying how to live. Or at least, how to survive.

It was here that I first learned how to step outside of myself and consider others. To weigh different views. To sit with discomfort. And somewhere in the quiet spaces between verses and voices, I found the beginning of something resembling a worldview.

Later, I’d fall in love with philosophy, proper philosophy. Kant, Descartes, Nietzsche. But I can trace the roots of that love back to those Saturday afternoons, tucked into a church hall with peeling walls and an open Bible, trying to understand what it meant to be good. And what it meant to be forgiven.

Hierarchy of Sin

There was an unspoken hierarchy of sin.

Adultery? A slip.

Gossip? Human weakness.

Pride? Dangerous, but forgivable.

But homosexuality?

That wasn’t just sin.

That was perversion.

Abomination.

War against God.

It was the kind of sin that provoked sermons. Full-length, chest-thumping sermons that turned ancient scripture into ammunition. The kind that made people sit straighter in their pews and glance sideways at the choir. It was the kind of sin you didn’t even need to confess, they’d already assigned it to you.

I came of age during a time when homosexuality wasn’t just a theological debate, it was a headline. A referendum. A prophecy. Across the Western world, marriage equality was gaining momentum. Under Obama, the U.S. was on the brink of legalisation. In the UK, the House of Commons was debating the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Bill.

But in church, these weren’t seen as civil rights.

They were omens.

Proof that society was rotting. That Satan was advancing. That we were living in the “final days” — and homosexuality, they claimed, was the clearest sign that the end was near.

Can you imagine that?

Being a teenager, just beginning to feel the early tremors of your desire, and hearing (from the pulpit, from the people you sang next to, from the very community that prayed over you) that you were the reason the world was ending.

That Jesus would return, not because the poor were suffering or the earth was burning, but because two men wanted to marry.

That your existence was so morally outrageous, it signalled the collapse of civilisation.

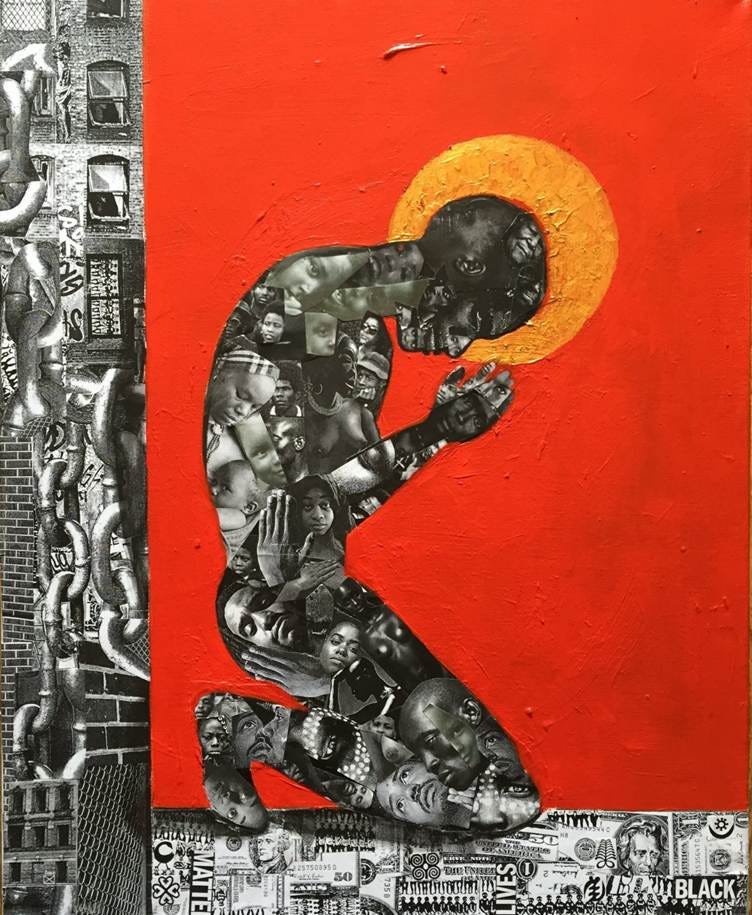

The weight of that messaging is hard to describe. It’s a heaviness. A kind of spiritual claustrophobia. A shame that seeps in slowly, word by word, glance by glance, until it’s woven into how you walk, how you speak, how you smile.

The harm wasn’t always loud. It was the silence after the punchline. The “amen” after the slur. The way no one ever corrected the elder who said, “I’d rather have a dead son than a gay one” or auntie who noted, “that’s not just sin — that’s sickness.”

And these weren’t strangers. These were people I served food to in our family home. People who laid hands on my shoulders in prayer. People who guided me during Scouts camping trips and passed me the mic to read scripture.

People who, moments earlier, had joined the choir in singing:

“I pray for you / You pray for me / I love you / I need you to survive.”

And then:

“I won't harm you with words from my mouth.”

But they did.

They were singing about love, but what I heard was a love with conditions.

A love that made space for the adulterer, the thief, the gossip, but not for me.

Not for what I hadn’t even said aloud.

I sang along anyway.

Because what else could I do?

At thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, I still needed to survive.

Devotion Was My Disguise

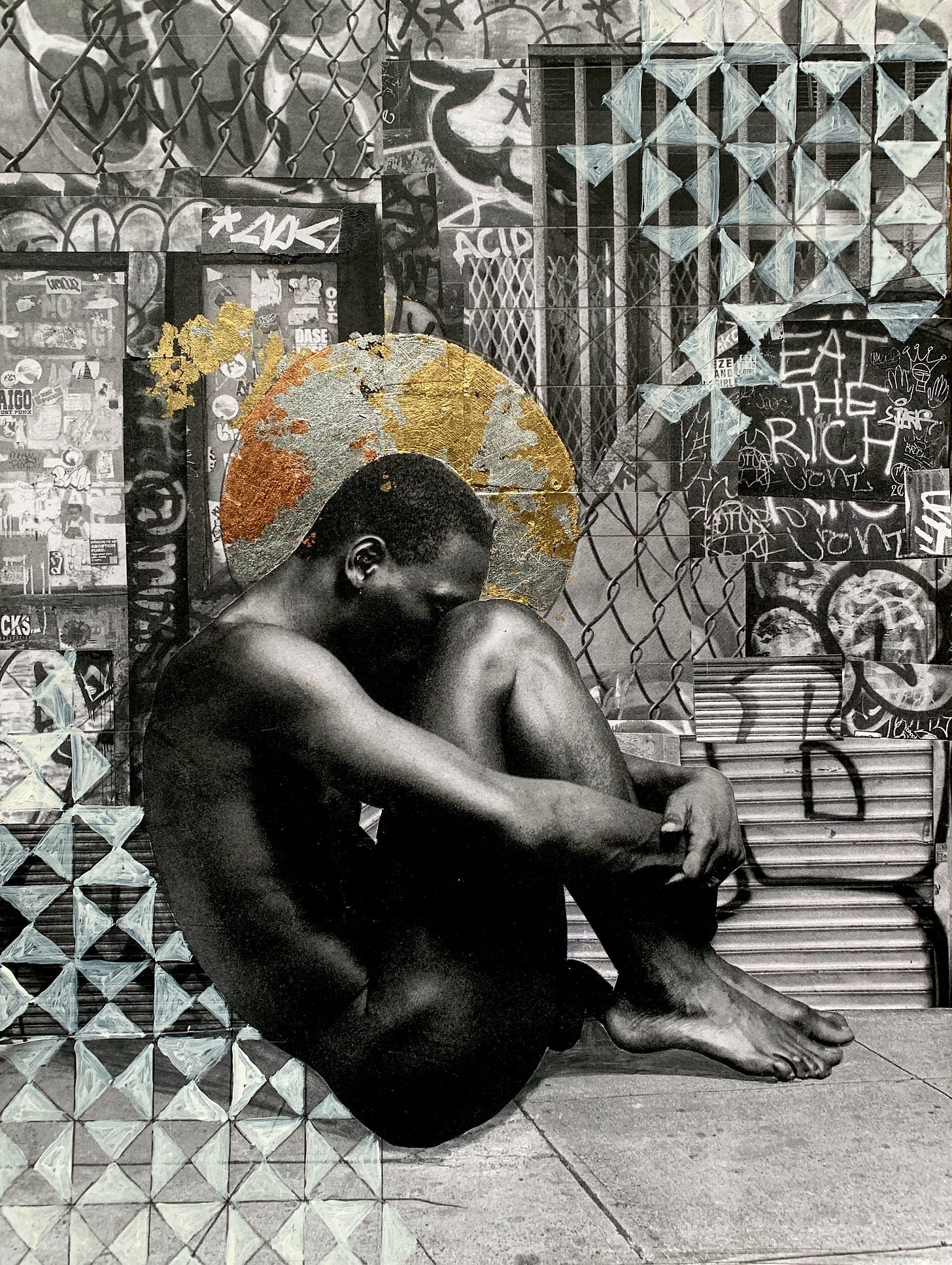

There’s a particular kind of fear that sets in when you realise the people who claim to love you would stop if they knew who you really were.

It’s not a loud fear.

It doesn’t scream.

It simmers.

Settles in your stomach.

Watches your hands.

Monitors your voice.

It teaches you to curate, to edit yourself in real time. To watch the way you laugh. To police the way you walk. To lower your voice just slightly when speaking to elders. To sit with your legs a little further apart, just in case.

Every gesture became a risk. Every eye a potential witness. I learned to exist under surveillance, not from others, but from myself.

And in the quiet, I prayed.

Not for joy. Not for strength. But for change.

I asked God to take it away the feelings, the thoughts, the part of me that felt like a stain.

I bargained: I’ll serve you more. I’ll pray harder. I’ll become someone better. Just… please.

Please fix me.

But He didn’t.

And when He didn’t, I turned on myself.

So I began to believe what I’d heard so many times before: that I was broken. That I was fundamentally disordered. That love (real, holy love) was not something someone like me was meant to receive.

I believed the sermons.

I believed the whispers.

And worst of all, I began to believe that I was the one doing the betraying.

That I was the problem.

That I was hurting my mother.

That I was contaminating the body of Christ.

That every smile I gave was a lie.

That every hymn I sang was a sin.

That simply being was a kind of treason against God, against my family, against the people who had loved

And still, I showed up every week.

Still sang. Still served. Still smiled.

Because at that age, it’s impossible to imagine a life outside the walls of your church, your school, your family. You can’t envision a future you haven’t seen. You can only try to survive the present.

I became fluent in performance. Devotion was my disguise.

Holy Enough to Pass

So I tried to out-church myself.

I dated girls. I joined the choir. I took more Bible study. I preached a sermon by the age of fourteen.

I read devotionals at dawn and volunteered for youth leadership. I learned how to pray in public; confident, measured, passionate but not performative. I learned how to pass.

If I could prove my holiness, maybe I could drown out the part of me that made me unworthy.

Maybe if I just worked harder, served more, looked the part perfectly, the feelings would retreat.

Maybe they’d stop being feelings altogether.

I made righteousness a routine.

I turned spirituality into a performance.

And I was good at it.

People praised me. They said I was mature for my age. Said I had a calling.

They invited me to mentor younger boys, to lead prayers before church luncheons.

No one suspected. That’s the part that still stings.

Because part of me was proud of the act. And part of me was horrified that it worked.

I became fluent in their expectations.

Praise with one eye open.

Hands raised high enough to be holy, never limp enough to be questioned.

I curated every part of myself to survive.

But survival came at a cost.

Because the more they believed in me, the more I felt like a fraud.

The louder they applauded, the lonelier I became.

It’s unsettling how quickly you learn to hate yourself in the name of love.

Reflection: On the Quiet Cost of Survival

Eventually, I left the church.

And in doing so, I left behind more than a building.

I left behind a set of friendships that had followed me from childhood into adolescence. I left behind uncles and aunties who had prayed over my exams, encouraged me to dream bigger, reminded me to eat more vegetables, told me I’d make a fine husband one day.

I left behind the certainty of routine, the rhythm of Sabbath, the structure of faith, the sacred pause at the end of each week.

I stopped sharing that ritual with my mother.

Stopped waking up early to hear her humming gospel as she got dressed.

Stopped watching her smile as we arrived together — proud, present, prepared.

She still believes. She always will.

But she no longer goes every week. Now it's once every few months. Quietly. Without ceremony.

And though she doesn’t say it outright, I know the questions linger:

Did I stray?

Did I fall away?

Am I lost?

But for me, the biggest loss wasn’t the church.

It was the Black community it held.

Because over time, I began to equate Blackness with rejection.

Not consciously at first. Not in language. But in instinct.

Even at university, surrounded by possibility (by people who might have understood me) I kept my distance. I avoided Black societies, Black student groups, Black church services. I told myself I was busy. I told myself I didn’t need them. But deep down, I was scared.

Scared that they’d look at me and see what I’d worked so hard to hide.

Scared they’d sense the boy I used to be, the one who wanted to belong but couldn’t.

Scared that they’d judge me, shame me, expose me, or worst of all… understand.

And so I chose exile.

Not because I didn’t want their friendship, but because I couldn’t bear the possibility of being let down again.

I rejected them before they could reject me.

I stayed polite. Kept it light. But I never let anyone in.

And that has cost me more than I can name.

Because in protecting myself, I became a stranger to my own people.

I taught myself how to smile while weeping inside.

I learned to trust no one and suspect everyone.

I learned to pretend everything was okay — to be holy, but never whole.

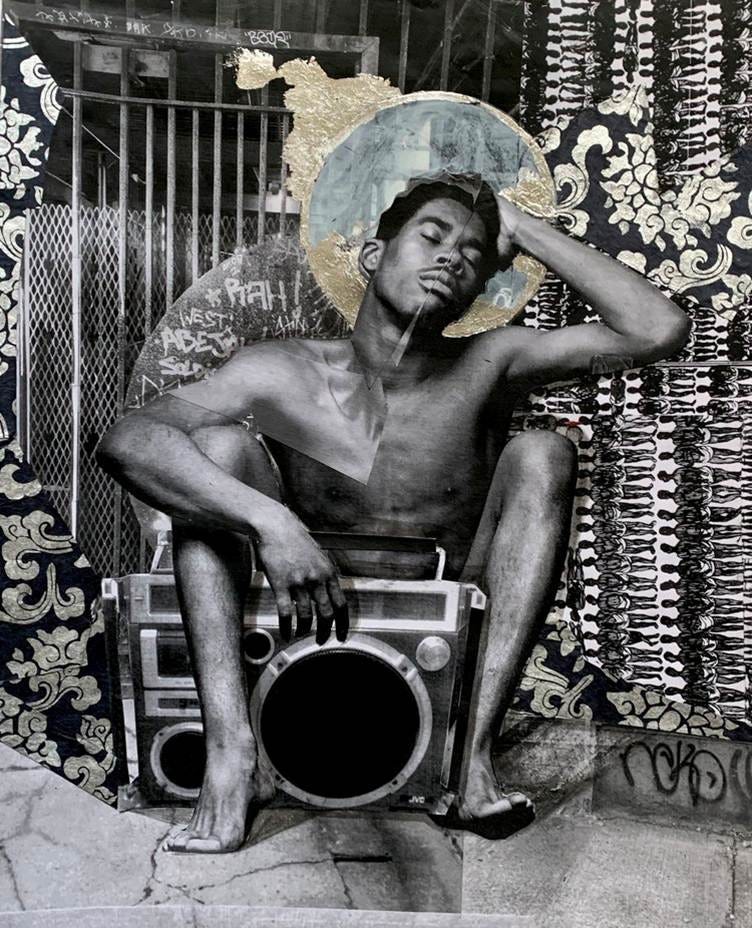

Now

Most Sundays, while I clean up and get ready for the week ahead (often with a hangover, often with the chaos of the night before still lingering in the kitchen) I put on my “Black Church” playlist.

It’s become my own kind of ritual.

No dress code. No sermon. No judgment.

Just me, and the music, and whatever’s left of the week.

I listen to Lift Up Your Voices by the Sunday Service Choir. Sometimes Never Would've Made It or a personal favorite Best in Me by Marvin Sapp. I let the sound take me back, not to the doctrine, but to the feeling. The warmth. The collective breath. The rhythm of something bigger than me moving through a room.

This time I’ve carved out, it’s not about going back.

It’s about remembering who I was, and making space for who I’m becoming.

I think about the childhood friends I lost because I was too afraid to let them love me.

I think about my mother, smiling so blissfully as the house filled with people she loved.

I think about the feeling of God moving through me — real, physical, undeniable — and how, even now, I sometimes still feel it.

Mostly, I use the time to reflect. To sit with the mess. To try and understand why I still flinch at closeness. Why I pull away before people get too close. Why some wounds never quite healed, just scabbed over, quietly, over time.

And I try to forgive.

I try to forgive the people who made me believe I was less than.

I try to forgive the boy who believed them.

I try to forgive the distance, the shame, the silence.

This isn’t resolution. It’s ritual.

A soft returning. A small, stubborn kind of hope.

I’m still figuring it out.

And for now, that’s enough.

P.S. If this piece made you feel something (even a little) I’d appreciate it if you shared it with someone you think might feel it too. Or leave a comment. Or just like it so I know I’m not whispering into the void. You know… standard digital intimacy.

Just about to share this on Bluesky but wanted to quickly say this here: this is absolutely stunning. There's so much I want to dwell on after reading this, but this part in particular:

'This isn’t resolution. It’s ritual.

A soft returning. A small, stubborn kind of hope.'

That is what I want to cling onto. I love your Sunday morning ritual. I hope I can do the same.