Downton Abbey Is Not a Governance Model

In response to The American Tribune’s latest exercise in nostalgia: “Why Liberalism Always Leads to Race Communism"

Preface: This Was Meant to Be Just a Note

I came across an essay on Substack recently titled “Why Liberalism Always Leads to Race Communism.” My initial instinct was to leave a quick “restacked with thoughts”-style response, maybe a line or two about how my blood bubbled slightly. But the more I sat with it, the more I realised it deserved more than a passing comment.

Because behind the confident phrasing, historical references, and performative outrage, there was something darker. Something more insidious. And what concerned me most wasn’t just the author’s rejection of the liberal world order—it was the intellectual dishonesty with which they framed their argument.

This essay is my full response. It isn’t about point-scoring or takedowns. It’s about refusing to let rhetoric stand in for truth, and calling out the danger in dressing up fear as philosophy.

On the Polished Panic of 'Race Communism'

First, credit where it’s due: the original essay published by The American Tribune was clearly researched and made no effort to hide its position. From what I gathered, it’s a far-right polemic that sees liberal democracy not as a safeguard of freedoms, but as a catalyst for societal collapse, cultural reversal, and demographic replacement. It’s a piece drenched in nostalgia for a lost social order: one where everyone “knew their place.”

It uses a cocktail of inflammatory examples, sweeping generalisations, and overwhelming footnotes to argue that liberalism is to blame for everything from mass migration to moral decay. In its world, equality is a lie, multiculturalism is a threat, and any attempt to redistribute power is framed as a prelude to civilisational suicide.

And then there’s the term itself—race communism. Let’s not pretend this is just spicy language. It’s a dog whistle turned air horn, lifted straight from the white supremacist playbook. This phrase, like its cousin cultural Marxism, isn’t really about political theory—it’s about fear. Fear that racial equality means personal loss. Fear that social progress must come at a cost to those who’ve long been insulated from it.

During desegregation, white supremacists routinely framed integration as a communist plot—“race communism” is just that paranoia in new packaging, a conspiracy cooked up to erode Western civilisation from within. Same energy. Different branding.

By slapping “communism” onto any effort to redistribute power or centre the marginalised, the author isn’t making an argument. They’re tapping into an old, racialised panic and dressing it up as philosophy. It’s not critique—it’s propaganda with a bibliography.

Now, I’m not here to say the liberal world order is flawless. It isn’t. There are real critiques to be made, some of which the essay points to (however selectively). But to use tragedy and trauma (like the horrific abuse of women in Europe) as justification to abandon modern democracy altogether?

That’s not just dishonest. It’s dangerous.

On the Intellectual Sleight of Hand

The most cunning part of the original piece isn’t the conclusion, it’s the way the argument is built.

By layering anecdote on top of anecdote, it overwhelms the reader with feeling before they can pause to think. By the time you’re halfway through, you’ve been bombarded with enough high-stakes horror stories that you might just nod along to the solution without realising you’ve been sold a fantasy.

But fantasy is the right word. What fuels this piece isn’t reason—it’s fear. Fear of loss. Nostalgia for control. Discomfort with complexity.

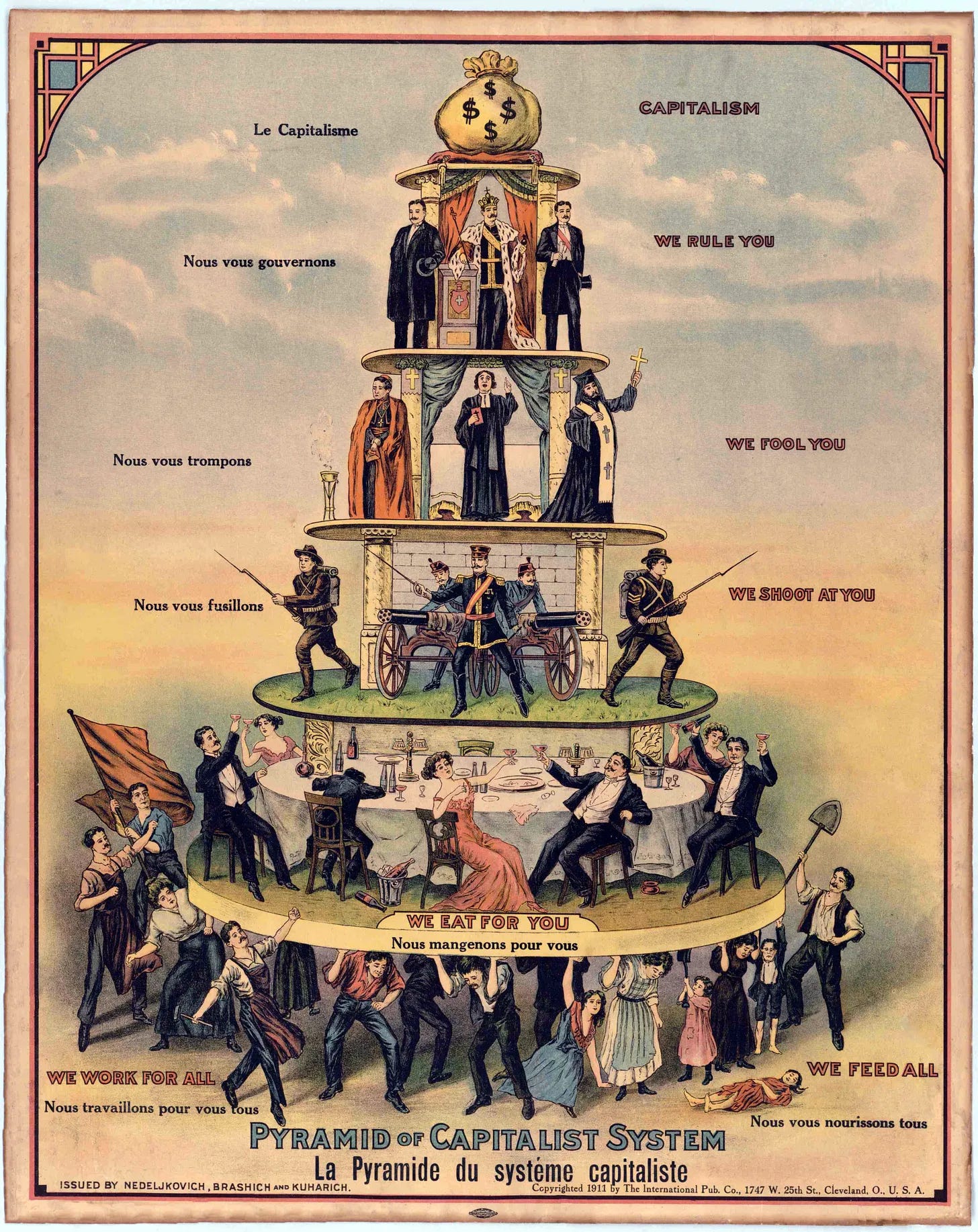

The argument goes something like this: liberalism promotes equality, but equality doesn’t exist in nature, therefore liberalism is a lie, and we should return to a society ruled by the “gentry class”—as if hierarchy will save us from ourselves.

That is not a critique. It’s a coping mechanism.

Part of the trick here is definitional. The author throws around “liberalism” like it’s a catch-all for every modern anxiety: immigration, gender politics, media bias, even economic decline. But what they describe isn’t liberalism, it’s a mood board of things they dislike. Liberalism, in its classical and modern forms, is a political philosophy rooted in individual rights, pluralism, limited government, and the rule of law. It is not the same thing as Marxism or socialism—in fact, liberal democracies have often been the loudest opponents of communism. But by blurring those lines, the essay tries to suggest that a world with any redistribution, inclusion, or dissent is teetering on the edge of totalitarian collapse.

That’s not political insight. That’s sleight of hand.

The Fantasy of Gentry Rule

Let’s entertain the idea for a moment.

The author calls for a return to gentry-led governance, seemingly imagining a world of gracious estates, honourable landowners, and benevolent paternalism. But here’s the historical reality:

Life for most people under the gentry was not orderly — it was brutal. Not moral — it was immovable. Not graceful — but graceless in its inequity.

You had:

No vote. No voice. No access to power.

Your labour existed to sustain someone else’s comfort.

Eviction, debtors’ prison, and moral policing were not exceptions, they were everyday tools.

If you were Black, colonised, Irish, queer, female (or any mix of the above) you were property, shadow, or shame.

Here’s a story. In 1834, the British Poor Law was amended to establish workhouses as the primary way to care for the impoverished. These were hellish institutions designed not to uplift, but to punish people for their poverty. Families were split apart. Men, women, and children were starved, humiliated, and worked to death under the guise of “moral improvement.” This was gentry morality in action: social control disguised as social order.

So, when I hear calls to return to that era, I have to ask: who do you imagine yourself to be in that world? The landowner? The judge? The gentleman?

And what happens if you’re wrong?

The Best of a Flawed Bunch

Let’s step back. Liberalism isn’t perfect. I don’t believe it is, and I don’t think anyone serious would claim it’s without contradiction. But of all the political frameworks history has offered us (fascism, feudalism, colonialism, communism) liberal democracy remains the best of a troubled lot.

It has:

Elevated life expectancy and reduced poverty globally

Enabled civil rights movements and enfranchised generations

Fostered innovation, cooperation, and cultural exchange

And helped produce the longest stretch of global peace in recent history through economic interdependence and soft diplomacy

It also gives us something the gentry class never did: the space to dissent. The author of the piece in hand and I both published our thoughts on public platforms. That’s liberalism at work.

So yes, critique the system. Demand better. But don’t pretend a world ruled by landed elites is anything but a retreat into hierarchy: designed not for justice, but for comfort. Yours.

A Thought Experiment for the Author

Before adopting the position outlined in Why Liberalism Always Leads to Race Communism, I invite you to try a simple thought experiment, borrowed from the political philosopher John Rawls.

Rawls asked: If you had to design a society without knowing your position in it—your race, gender, class, health, or intelligence—what kind of society would you create?

This is the veil of ignorance. Behind it, we are all equal in uncertainty, and so we design systems that protect the vulnerable, not the already-powerful.

So, I ask you directly:

If you didn’t know who you’d be in the social order, would you still choose to live in a world ruled by the gentry?

Would you risk being born a sharecropper? A servant? A colonised subject?

Would you want to be the queer son of a tenant farmer in Victorian England?

If the answer is no (and I suspect it is) then perhaps the real question isn’t whether liberalism has failed, but whether you're willing to share power at all.

Where That Leaves Us

If a better system than liberal democracy exists, I’m open to hearing it. But the essay at hand doesn’t offer one. It offers a regression. A fantasy built on fear and hierarchy.

I’d rather live in a flawed world of freedom—coexisting with those different from me—than in one where hierarchy dictates who matters.

Because if you truly believe in equality, you must be willing to live in a world where you might not come out on top.

And if you can’t bear that thought, then this was never about governance at all.

P.S. If this stirred something—anger, agreement, curiosity—feel free to share your thoughts, and/or share it with a mate or two.

Okay, but not great. How can someone who is evidently not well-read in the topics of feudalism and European history claim that liberal democracy is, in the Churchillian mode, the "best of a bad bunch"? Of course, some feudal states were better than others (Pre-Revolutionary France and Russia were particularly awful), but there's a reason symphonies and frescoes were produced back then, while we get pop music and DeviantArt. Now, I also agree that thinkers like Yarvin and Hoppe and Rand fundamentally misconstrue the universe in many ways, and I tend to take issue with the AnCap movement on a purely spiritual level (the modern movement can be attributed to the result of a lot of lonesome autistic people who don't understand human beings trying to reconcile their rejection from mainstream society with a supposed ability to parse reality at a deeper level than normies - Moldbug says as much); but this isn't so much a polemic as it is an offhand dismissal, a "look at these antiquated old dinosaurs and their fuddy-duddy ideas". Sorry, but that line of attack just doesn't hold water anymore.

Found this while tumbling down a Reddit rabbit hole and I’ve got to say......worth the detour.

I read the original “Why Liberalism Always Leads to Race Communism” after seeing this, and (if I’m honest) I was nodding along at first. It’s persuasive in that confident, footnote-heavy way tapping into that nagging feeling that something’s gone off in the world (and something deffo has gone off tbf). But this response is what actually made me pause. It doesn’t just argue back, it zooms out and asks the real question: if you didn’t know where you’d land in the pecking order, would you still want to defend a system where the ultra wealthy and people born into positions of power dominate? (deep)

I have to admit this is denser than my usual Reddit fare, but surprisingly easy to sit with. The Rawls thought experiment brought me straight back to A-level philosophy. And the bit about the workhouses…grim but spot on. Really cut through the romanticism and made it clear that “order” back then usually meant punishment for being poor. It reframed the whole original essay as less about stability and more about control!

Did anyone else get halfway through the original thinking “hmm, fair enough”... before realising they were being sold Downton Abbey with a side of authoritarianism?